Here’s a fun fact you can share during your next happy hour: you can get drunk off of vanilla extract. We’re not joking. Per Bon Appétit, downing the fragrant brown liquid can lead to a buzz, not unlike the one you get from some of your favorite spirits — though it will take more than a standard 1.5 ounce shot to get you sloshed (via the NIAAA). According to Kitchen At The Store, one typically needs to drink about four to five ounces of pure vanilla extract to start feeling drunk.

That definitely does not sound as appealing as sipping on a margarita, nor do we recommend doing it (one Reddit user says it will lead to “the worst hangover of your life”). But it has been done, and more than once. Back in 2019, NBC reported that a Connecticut woman was issued a DUI after drinking several bottles of the baking ingredient.

The same year, a high school in Georgia had to put out a warning to parents after they found that kids were spiking their morning coffee with Pure Bourbon Vanilla Extract from Trader Joe’s, causing one student to be hospitalized (via News10).

So, what is it that makes vanilla extract so potent? Just a little thing called 35 percent alcohol content, which is the minimum requirement set by the Food and Drug Administration for vanilla extract to actually be considered vanilla extract (via Taste of Home).

That’s right, the tiny bottle of vanilla extract sitting in your spice cabinet that goes into cakes and cookies has an alcohol content of 35 percent, the same amount found in liquors like Jägermeister and Captain Morgan’s rum (via Bon Appétit). However, you don’t have to take a trip to a special store or show your I.D. to purchase the stuff.

According to Bon Appétit, a law that dates back to Prohibition is the reason why vanilla extract is stocked at the supermarket rather than liquor stores. The story goes that when the United States banned alcohol with the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919, the Flavors and Extract Manufacturers Association (or FEMA) lobbied congressmen to exempt their products from being considered one of the banned substances so as not to “destroy our legitimate businesses.”

Fortunately for them, the government listened and exempted “nonpotable” flavor extracts from being outlawed with the rest of the alcoholic beverages prohibited under the Volstead Act enacted in 1920. This also set up extracts of vanilla and other flavors to be regulated by the FDA as a “food product” after Prohibition ended, which is why you can pick it up at the grocery store when you want to make a batch of chocolate chip cookies.

That being said, if you are looking to have a little fun (responsibly!), please, don’t pour up a glass of straight vanilla extract just because it’s available and has the ability to do the trick. Maybe try some nice RumChata instead.

If you’ve ever wondered why on earth you should buy pure vanilla extract at $29.99 for 12 ounces when you could get the fake stuff for $6.49 a GALLON, look no further. There are real differences between pure vanilla, made from delicate orchid beans (yes), and artificial vanilla, literally made from petrochemicals and wood (via Scientific American).

Vanilla extract may be a splurge, but it’s usually worth the dough (via Kitchn). However, you can still use artificial vanilla in recipes where other flavors dominate — why use the good stuff where no one will taste the difference?

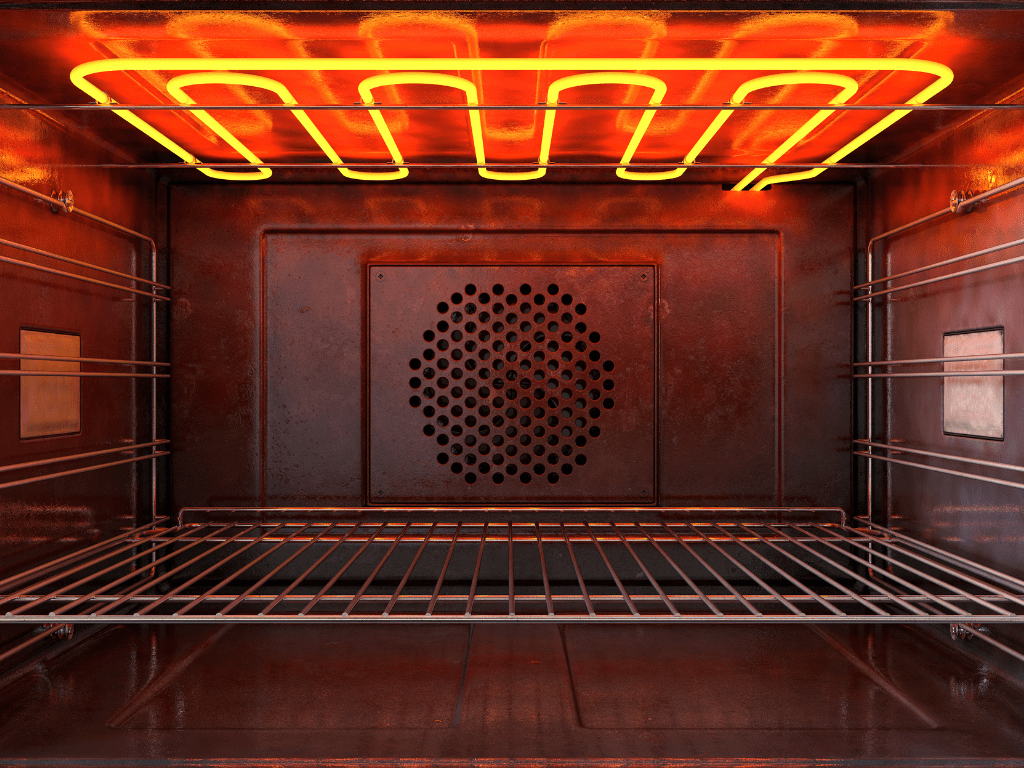

So here’s how pure vanilla extract is made: vanilla beans soak in alcohol to extract their unique flavor, and according to the FDA, you can only call your product vanilla extract if it’s up to their specifications (via The Spruce Eats): no less than 13.35 ounces of vanilla beans per gallon and no less than 35 percent ethyl alcohol (via FDA).

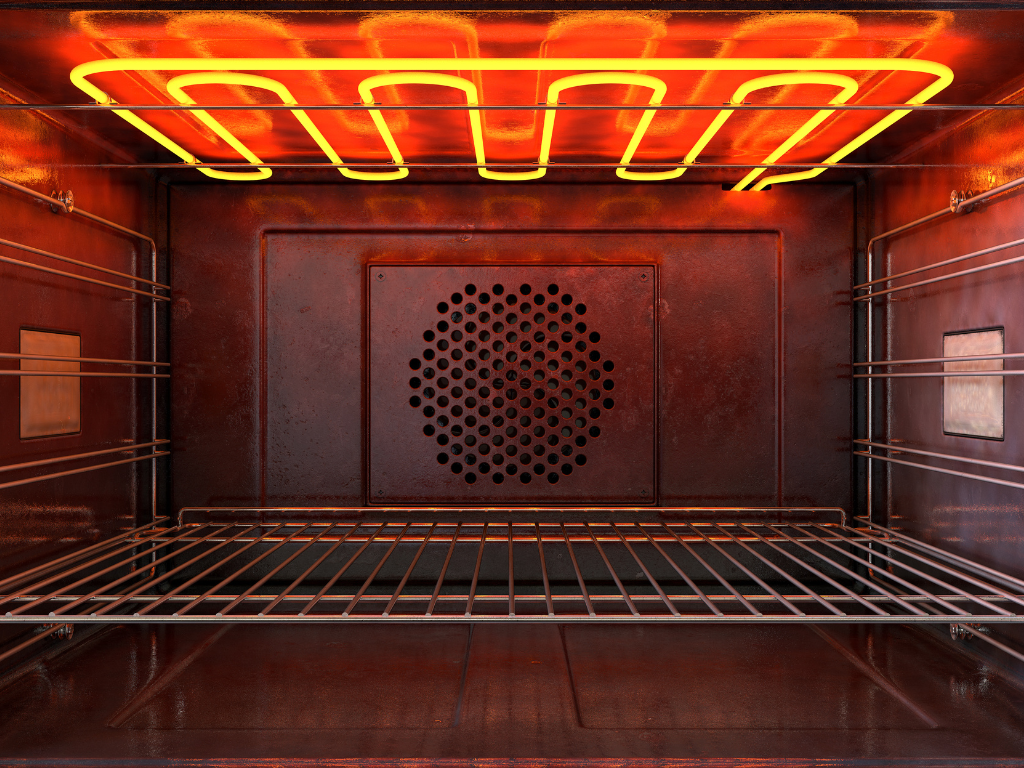

Pure vanilla extract is so pricey because vanilla beans come from an orchid that is very labor-intensive to grow and is mostly found in just a few hot, humid locales like Madagascar (via Huffington Post). The pods grow once the orchid is hand-pollinated and blooms, then put into hot water and laid out to dry for months. Only then does the extraction process begin.

Most imitation vanilla, on the other hand, is mostly made with vanillin made from guaiacol, which is a precursor to a petrochemical (or a chemical derived from refining oil or gas), according to Scientific American. Yup.

The rest is produced with lignin, which comes from wood (via Science Direct). That’s why it’s so cheap. And according to the Spruce Eats, imitation vanilla products often have a somewhat bitter after taste for people with sensitive palates. So, pro bakers say, if you’re going for a vanilla custard, vanilla frosting, or vanilla cake — opt for the more delicate pure vanilla.

The good news is, you probably won’t be able to tell the difference between the two versions in a dessert whose primary flavor isn’t vanilla, like chocolate, spice cakes, or cookies with a lot of mix-ins. One expert recommended to The Kitchn to use a healthy balance between the two: save “the good stuff” for when vanilla flavor needs to shine, but in recipes with more bold flavors, artificial will do.

Vanilla is loved the world over. It is one of the most popular flavors in the ice cream world, a celebrity among desserts, and a fixture among bakers overall. Vanilla has a warm, woody, floral taste that is exquisite on its own and phenomenal as a supporting ingredient for other flavors. Vanilla is versatile, complex, and well-loved, but vanilla extract, specifically, is actually a relatively finicky ingredient.

Vanilla extract shelves in baking aisles at grocery stores are stuffed with dozens of different options across a wide scale of varying price points, and every vanilla flavoring agent is not created equally. So, what is the difference between different types of vanillas? What makes vanilla Tahitian, or Mexican, or French, or artificial, or all-natural?

What makes vanilla extract an “extract” and not a flavoring? A number of legal distinctions, for one, define what it means to be pure vanilla extract. Pure vanilla extract, in the baking world, is the platonic ideal of vanilla flavoring. It’s what every vanilla strives to be. Read on to discover exactly why vanilla extract is so sought-after.

Vanilla is the name for the flavor derived from vanillin, a chemical compound that, when mixed with several other more minor components, results in a beloved ingredient for cooking and baking. Vanilla extract is obtained when the pods of a vanilla plant, also known as vanilla beans, are steeped in alcohol.

In vanilla extract, scientists have discovered hundreds of taste and aroma compounds that layer on top of each other to create the complex flavor of vanilla extract. That said, many of these minor compounds are heat sensitive and ultimately do not make it to the final product of a baking project. That is to say, in part due to vanilla extract’s alcoholic nature, between the “cake batter” and “piece of cake” stages of a baked good, much of the vanilla extract components are baked off, resulting in a full, deep vanillin flavor dominating every bite.

Even though much of the extract components bake off, the complex layered flavor of vanilla extract still provides a deeper and more aromatic flavor than simple vanillin flavor.

Is vanilla essence the same as vanilla extract?

Vanilla extracts and vanilla essences differ in that the former is a strong, thick liquid made of alcohol and vanilla beans, while the latter is a thin liquid made primarily of water. Vanilla essence is typically made with artificial vanillin.

Vanilla extract vs. imitation vanilla extract: what’s the difference?

In cooking and baking, all vanilla extract is not created equal. Imitation vanilla extract is “any preparation of one or more synthetic vanillin compounds together with any diluents and/or fillers provided for in parts 184 or 185, and with or without the addition of a coloring agent,” according to FDA regulations.

Can you use vanilla essence instead of vanilla extract?

Not all vanilla essences are created equal. Some synthetic versions of vanillin, which does not taste like real vanilla, may cause allergic reactions in some consumers. Proponents of artificial vanilla argue that synthetic vanillin is safer than natural vanillin because there is less risk of adulteration by other plant materials and because it avoids the labor-intensive process of hand pollination.

Vanilla extract vs. pure vanilla: what’s the difference?

Vanilla extract comes from an orchid bush native to Mexico, Papua New Guinea, and the islands off the coast of Madagascar; it’s expensive because it’s labor intensive to grow, which makes up much of its price tag. Pure vanilla is a combination of the molasses inside the pod and the flavor and aroma compounds that are extracted from it.

Vanilla extract vs. true vanilla: what’s the difference?

True vanilla is made from whole pods, not extracts. It has a sweeter and more aromatic taste than extract but is not as strong or sweet as pure vanilla extract. True vanilla extracts and essences are available in dark brown, clear, light brown and white varieties.

Can you substitute vanilla essence for vanilla estract?

The answer is maybe. If a recipe calls for vanilla extract, you can substitute vanilla essence, but it may not have the same full flavor as extract. Check the recipe’s ingredient list to make sure the recipe will hold up with the substitution.

Is homemade vanilla extract better than store-bought?

The short answer is yes because making your own vanilla extract is easy and doesn’t require a lengthy process. The longer answer is also yes because homemade vanilla extract allows you to control the alcohol content and choose which beans you use based on your preference for flavor selection and budget (see below for more about this—or watch this quick video tutorial).

Vanilla extract has complex flavor profiles including vanillin, ethyl vanillin, dihydrovanillin, vanillic acid and other compounds like coumarin (or possibly phenylpropionon), d-limonene, nerol acetate and others. Depending on the type of vanilla used, it can also have hints of oak and spices. The amount of real vanilla in a bottle will change over time with temperature changes and changes in the level of alcohol in the liquid.